Stéphane Bruchet

_______________________[Back to project page]

The cultural landscape

of the Boggeragh Uplands

Stéphane Bruchet

︎Archives- The lane

- Uplands

- The Gearagh

- Seen City

- flow

- Oilean

︎Contact

The lane | 2020

First lockdown.

I went looking for sanity, I found peace.

And made 10 little books at home for the neighbours of the lane.

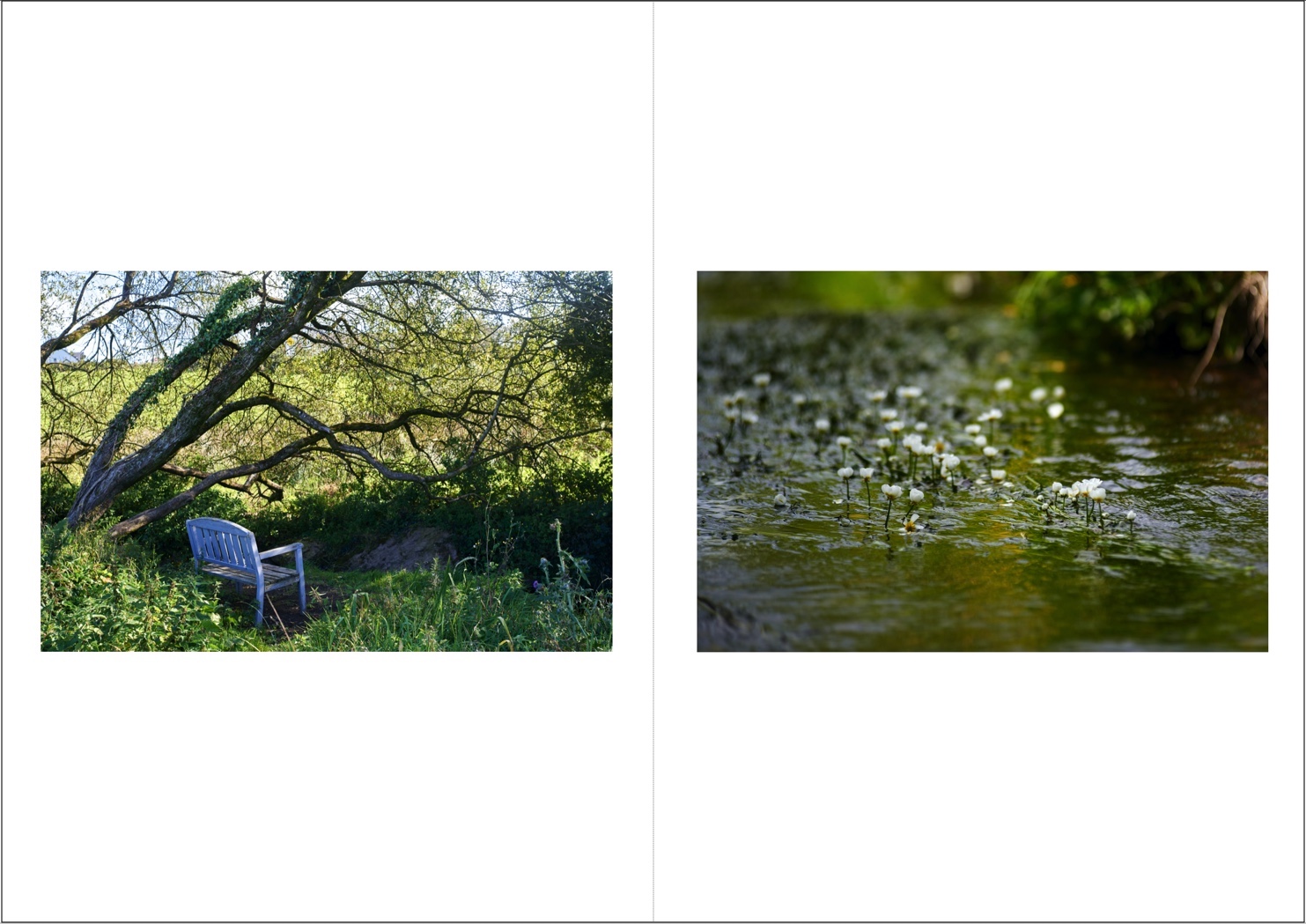

Uplands | 2019

Ballincollig Library

Stéphane Bruchet

︎Archives- The lane

- Uplands

- The Gearagh

- Seen City

- flow

- Oilean

︎Contact

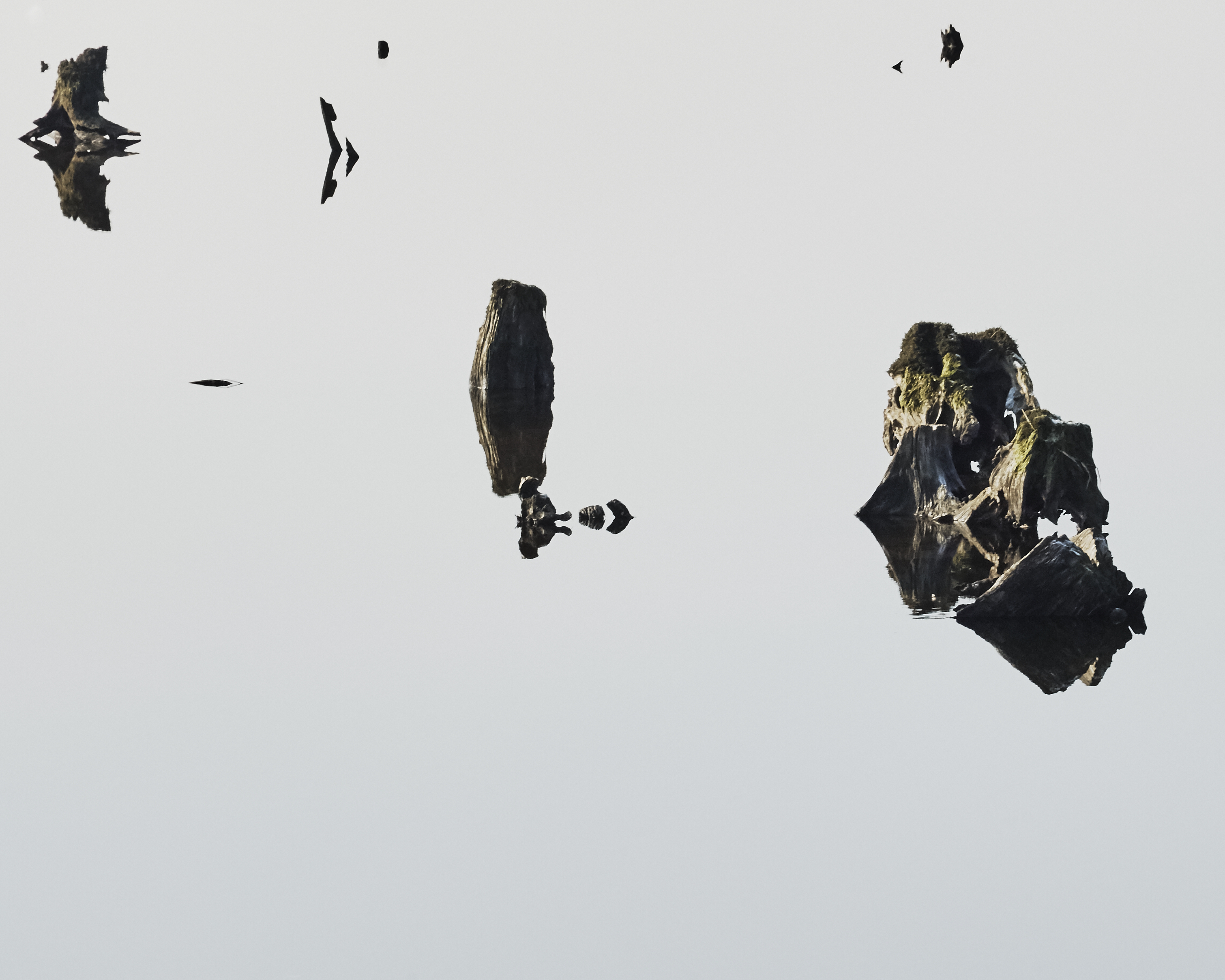

The Gearagh | 2017

The Gearagh is the only post glacial alluvial forest in Western Europe and forms a delta on the river Lee in County Cork. The Irish name, An Ghaoraidh means the wooded river.

In the 50s, the construction of 2 reservoirs downstream to generate electricity and regulate the flow of the river resulted in the destruction of 60% of the Gearagh’s specific ecosystem.

The difficult task of falling the trees in this network of streams took 3 years and as a result, tree stumps were left in place and covered by the rising water of the reservoir.

The stumps would appear and disappear as the water levels were regulated.

The Gearagh is now a protected site.

Shows:

︎ Fintan Lynch air, Kinsale - 2017 (full series)

︎ Halftone Print fair, Dublin - 2015 (3 selected prints)

Print Details:

Hahnemühle rag 308 gsm

Individual prints| size: 20x25 cm | Edition of 7 (+1 AP)

Full series (As presented)| size: 80x95 cm | Edition of 4 (+1 AP)